“I have never lost my faith to what seems to me is a materialism that leads nowhere—nowhere of value, anyway. I have never met a super-wealthy person for whom money obviated any of the basic challenges of finding happiness in the material world.”

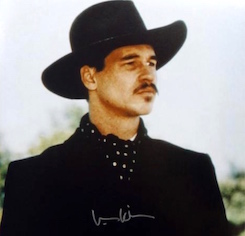

Guess who wrote that in his 2020 memoir, now a New York Times bestseller? Perhaps surprising to you, it is none other than Val Kilmer.

His book is entitled I’m Your Huckleberry, a riff on the most notable quote in a movie chock-full of notable quotes: the 1993 cinematic wonder, Tombstone. Kilmer and Kurt Russell rewrote Kevin Jarre’s screenplay fairly significantly, he claims, to help it pass muster with George P. Cosmatos, the demanding director of the film.

Since he was a boy, Val Kilmer lived twice as fast as anyone else, so what you have with this book is an honest and revealing memoir by a 120-year-old Hollywood titan. He probably tried harder in some of his films than anyone else who could be considered his equal. He loved and admired directors such as Tony Scott and Oliver Stone who were as intense and perfectionistic as he is/was. Indeed, like the ambitious and visionary Greek mythical figure Icarus, Kilmer’s meteoric rise as an actor of astounding ability and his subsequent plummeting back down to the hard Earth are equally remarkable.

In Tinseltown, perhaps more than any other since Rome, only the strong survive, and no one—not an acting legend and not an Emperor—can outpace Time forever.

First, this image of Icarus having fallen back to Earth:

That is one astounding piece of art. I don’t know where is lies or what it’s called, but it features the Greek mythological figure, Icarus, who is ambitious, hubristic, and daring—to a fault. He constructs wings made of wood, feathers, and wax, and jumps off a cliff, hoping to fly up to the heavens. Like Kilmer, he succeeds—for a time—and then, as the nearing sun melts the wax of his wings, he tumbles to the Earth.

Such is the story of Val Kilmer, I think. He himself admits as much: “Some of us know how to walk away–from money, from heartache. The Kilmers, though stay–and then stay some more.” He is noting that he and his father were most remarkable, and not very moderate. Indeed, reflecting on how he screwed things up with the wonderful person, actress Daryl Hannah, he writes: “I believe in moving forward toward the ultimate goal: unification with a loving God. At the same time, I continue to lead my life on the run. Lord knows I’ve suffered heartache with women. But Daryl was by far the most painful of all.” Tragic character is how he kind of comes across in the book. Unlike Icarus, he hasn’t fallen to Earth, dead, but he was put on his heels by throat cancer (due, presumably, to smoking and his “life on the run”). It felt as I read the book that he was pushing the limits too far, for too long. He is mortal, after all.

But we needn’t dwell on the negatives. Like Icarus, Val’s choices were his own—the women, the roles, the religiosity, the smoking and the all-nighters, the locking horns with Hollywood directors. I think it is fair to picture Kilmer not as a fool—though he calls himself one a couple times in the book when he fails to knit together a lasting love relationship with the likes of Carly Simon or Ellen Barkin or Darryl Hannah because of his dark side—but as one who lived life just how he wanted. He was gorgeous, talented, courageous, individualistic, loving, spiritual, disciplined, and free-spirited; that he eventually got too close to the sun is not the most important or remarkable aspect of his story. At bottom, what a life this man lived!

Val had Hollywood in the palm of his hand starting with Top Gun and probably ending with Kiss Kiss/Bang Bang, and certainly reaching a crescendo with Batman Forever and The Saint. My favorites are The Doors, Tombstone, The Salton Sea, Willow, and The Saint, but he must have been in 50 films and just as many plays—including his baby, Citizen Twain, based on the life and writings of America’s satirist extraordinaire, Mark Twain. Despite having turned 60 and been completely and deeply affected by throat cancer, he is in the much-anticipated sequel, Top Gun: Maverick.

Val Kilmer Quotes from his Memoir, I’m Your Huckleberry. In it, He Seems Part Icarus, Part Marcus Aurelius:

“The experience of acting Shakespeare makes clear, throughout his impossibly-diverse attempts to clarify and elucidate our souls to us, that we’ve got the best, most condensed shot at understanding the truth of our very spirit through a display or reflection of actions that reveal our habits and folly as well as our nobility and higher strivings.”

“Mark Twain struck a visceral chord, perhaps a lifetime’s worth of chords. He railed against divisions of race, class, and age. He was coarse and brilliant and funny and irreverent and honest and—as someone who deserted the Confederate army two weeks after joining—a famous coward. I came to love all these distinctions.”

“[My grandfather, a mountain-man/prospector in the New Mexico wilderness] adhered to a sacred code that in the wilds, everyone is connected and responsible for each other. You do whatever your neighbor needs at whatever cost to you—a bit more than just bringing over a pie when a neighbor moves in. It’s a beautiful way of living. I have both offered and received this remarkable kindness from people for all the decades I have lived in the New Mexico wilderness. You are valued by what you do, not who you are or how many cars (or backhoes) you own.”

At age fourteen I was asked to play a small part in “The Stingiest Man in Town”, a musical about Scrooge. Next came the English comedy “The Mouse That Roared”, where I got to employ a German accent that elicited great laughter. That was the moment I experienced the enormous satisfaction of making hundreds of people laugh. Angels were kissing me all over. I felt different; I felt present in a way I had never felt before. …I could always entertain family and friends, but these audience members were strangers I had touched, and having been touched, they were strangers no longer. That transformation forged my future.

“On stage, I felt at home—and not at home. I had some innate confidence that I could turn myself into a character. In my earliest acting experiences, I saw this contradiction cropping up everywhere. I was, and was not, the character I played. The character went through me, and therefore was me, even as I went through the character and became him. Pieces of me and pieces of him merged. …The excitement was extraordinary.”

[My brother] Wesley’s death changed everything [when I was a teenager]. I tried to accept the idea, substantiated by reading Shakespeare, that tragedy is not without its gifts. But acceptance was and always will be onerous. As I write these words, I yearn for Wesley’s company. I want my brother alive—physically, not just spiritually.

“From the moment I stepped on campus, I was skeptical. The name itself bothered me. You were instructed to say THE Julliard School. You could not omit the THE. My attitude was, To hell with the THE! A school’s A school; just as there isn’t THE truth, there’s A truth. …Opening day was brutal. It didn’t help to be told that one of the people sitting next to us wouldn’t be there next year. What was this—the Marines? It was suggested that of the thirty or so kids in this new class, only half would survive.”

“In the material world, my primary drive is artistic. It isn’t that I don’t like or want money. I like it just fine and I want it; I love buying stuff and I love giving away stuff. But I didn’t become an actor and writer with the idea of making a fortune. I did it because it was my nature to do so; I never even made the choice.”

[In Top Gun], I grew more serious about my on-screen character [Tom “Iceman” Kazansky]. Even though I could play an arrogant jerk in my sleep, I actually found myself looking deep into this guy. What made him so arrogant? The question intrigued me. I thought about it for long stretches of time, and I dreamed about it. …I became so obsessed that at one point, in my trailer, I actually saw—the way Macbeth saw the ghost of Banquo—Iceman’s father, the man (my imagination inferred) who ignored his son to the point where he was driven to prove himself as the absolute, ideal man.

“People assumed I took drugs to emulated Jim Morrison’s state of mind. I did the opposite; I stayed super clean and jogged ten miles a day. To get into Jim’s cloudy mind, I required absolute clarity.”

“Gaining a reputation as a cooperative thespian is not a bad thing. I do not condemn my brothers and sisters who have developed personalities pleasing to directors. I have, in fact, pleased dozens of directors. Others I have not. And when I have not, it isn’t through ego; it’s simply because I have connected with a character and must honor that connection.”

“Now, I was dealing with the blues that come after a film is finished. It’s a postpartum kind of blues. Artists can become severely depressed when they’re not performing. What is this business of giving our bodies and souls over to magic such that we have nothing left for ourselves? …Maybe my feelings post-Doors came from a deep knowledge. Maybe I feared no project would ever be quite as special. …What would life look like after touching the pearly gates—pretending to be normal after getting a taste of heaven?”

Learn more about the Greek myth of Icarus and Daedalus, where hubris, rather than moderation, drives the characters: LINK

“Boy, do I pray about the idea often that needing some physical thing more than the unity of the spirit, more than the principles of mind, soul, life, truth, Love. Now I am in my sixties. Every time I speak, I must put a finger to the aperture in my throat to be understood. Cher says I remain adorable, but Cher says that to a lot of guys! But like [my hero, Marlon] Brando, my body has taken on a much different form. Also like Brando, I choose to accept this form with equanimity.”

“Years later [after I tried and failed to win Cindy Crawford’s enduring love], I was rescued from an icy solitude by another angel. Perhaps the most soulful and serious of them all. Angelina Jolie. When people ask me what she is like, I always say she’s like other women and other superstars, but just more. More gorgeous. More tragic. Wiser. More grounded. Is it worth it–worth knowing people who require weeks of effort to understand even a little? Yes. These paradigms of power and prowess are the women who have inspired men throughout history to fight battles, build nations, and leave their wives behind. I melt at the sight of women like these. I am a hopeless romantic.”

We sing along with the impossible yearning and tap our toes to the beat. No matter what we possess, most of us want more, more, more. Is this the survival instinct and the essence of the human being? Or is it just capitalism?

“In the aftermath of that relationship, I sought peace of mind by reading, reading, reading. Books have always sustained me, especially when the blues blow through like a hurricane.”

At the start of the 21st century, I felt myself drawn to Mark Twain in a way I hadn’t experienced since childhood. Head-on, he addressed the major issues that have haunted America then–and haunt it now: the hypocrisy of polite society, the pernicious evils of racism, the essential artistic [urge] to rail against conformity and find unfettered expression in biting wit and outrageous drama. …The genius of his literary enterprise floored me and had me reading Train–all of it–day and night. Like his books, he was both a comic and a tragic figure. He was the most famous American of his time. He earned and lost fortunes…. Twain understood the troubled souls of this nation’s citizens with the acuity of a devilish saint. He was a lonely leader of a tribe looking for hope. In that regard, he reminds me of Moses.

“In my mind, I retired. I decided that my priorities would undergo a massive cognitive shift. In the words of Thoreau, ‘Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth.'”

“As I’ve said concerning artistic projects, I am subject to impetuousness. The same goes for romance. I take it seriously. I accept these liaisons as lovely interludes; some lasted for months, some for years. All last forever.”

“I knew which movies would be good before I took the roles (I knew exactly how much money they would make). I’ve always been good at numbers games. But I had a life outside of work. Twain says, ‘The world owes you nothing; it was here first.’ We all have to pay our dues. It just so happens I had to pay mine at a strange, warped midpoint in my life, rather than right at the beginning.”

On p. 287, Kilmer states “Mark Twain once said, ‘The fear of death follows from the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time.'”

“My speech was compromised, but I was seeing and feeling things I had never seen or felt before.

Why? I suppose that’s just the way the world works.

And we just do not know what is ahead.

Uncertainty, I realized, is holy.

Death may come, or Bob Dylan may show up.

And there isn’t much we can do about it. Except sit back, breathe, and enjoy looking at the sky.”

“When finally [Daryl Hannah] and I broke up, I cried every single days for a half-year at least, until I became very concerned about my kids seeing me that way. I thought, Grow up! I couldn’t do it anymore, and I couldn’t do it to them. I am still in love with Daryl, but…it was no great surprise that she wound up marrying Neil Young. It was a matter of one giant attracting another. Those kind of rip-your-heart-out relationships that had become so normal for me were just no good anymore. Love was at the core of my life, that was for sure, but was it the kind of Love that was building toward a life of service?“

((I appreciate that shout-out for Values of the Wise’s main angle, “building a life of value“!))

Perhaps, like Icarus, the man who dated all the most beautiful women, from Cindy Crawford to Cher, and stayed up late and smoked and basically acted kind of manic, Val Kilmer, has fallen from the heights where there is nothing but blue, rarefied air, and the invincible sun. He doesn’t seem to believe that he would have done it any other way than the route his chose. But, I assume he probably would not have smoked, at least!

Indeed, according to myth, the young and heedless Icarus fell to the Earth while trying to soar higher and higher, and died a horrible death. Having spent the last few years as Mark Train, and now not hung up on finding “perfect love” from “perfect women”, living a more modest lifestyle, and doing lots of art, the post-cancer Val Kilmer might be the richest one yet—in ways that money can’t buy. I hope so, I do love the guy.

I came away from the book duly impressed by all the high points in Val’s life. He really did fly very close to the sun, as many of history’s greatest individuals did. I know that the loss of one’s normal speaking voice is not the end of the world, and Val’s attitude is mostly that of a positive and self-actualized perspective. But just for me personally, I feel a deep sense of sadness when I reflect on the man who started out in movies like Real Genius and an after-school special in which he plays a teen who drinks to much (opposite a very young and alluring Michelle Pfeiffer, by the way). Kilmer’s long arc from boy genius rebelling at Julliard to his current, post-cancer physical state is breath-taking. It draws to mind the decline and decay that hurt me so much when I saw it first-hand with my father, with John Marshall, and with my wonderful dog of ten years, Atlas. His story speaks loudly and declaratively to the absurdity of existence, the human condition, and the relentlessness of time. As the character Sir Davos said in Game of Thrones, “Nothing fucks you harder than Time.”

I think I get now why Icarus and Daedelus wanted to break the Earth’s chains and fly: to escape the fears that prey on the human mind due to the nature of existence.

Maybe sorrow or pity are not proper emotions when reacting to Kilmer’s book, and life; he may be “on the ropes” when it comes to age or Hollywood or cancer, but he has been seizing the day for decades, and no mortal can expect to outrun (outfly?) merciless Time. Ω

The New York Times recently interviewed him (LINK). I can’t say it’s concise. Here are a few snippets:

“Before you can understand the story of what happened to Val Kilmer, you have to determine for yourself who he was in the first place. Trying to compare him to any movie star working either now or then will fry your mental circuit board: He was an upwardly mobile conventional movie star; he was equally a fringe weirdo who would soon disappear.”

“He can put it all together now far better than he ever could back then. He’d had his pick of roles; he was being offered lucrative franchises. His talent was in doubt by absolutely no one. His gift was both so overt and so subtle that he was the most memorable part of the movies he merely supported. And yet suddenly he was radioactive.”

“No, the problem was that he had been trained to inhabit any role he could find himself in; he just couldn’t find himself in a normie, and by the time Kilmer came online as a movie star, normie roles were all there were, the ’90s standard-issue regular guy in extraordinary circumstances. Kilmer’s greatest roles were always supporting characters. The roles of troubled men with broken souls went to the other guys because who would believe that a guy who looked like him had real troubles or a broken soul?”

“But he couldn’t reverse course and bow out, either. By then, he had been seduced by a lifestyle. Look at his face in a tabloid photo of him and Cher circa 1984. Look at the pride; look how much he enjoyed being on Cher’s arm. It reminds him of something he heard once: ‘God wants us to walk, but the devil sends a limo’.”

“That’s a pretty happy ending to a sad story. The lesson here is Val Kilmer’s perpetual lesson, that if you have enough faith — if you can take the long view and remember that things will work out — destiny takes over. I say that to prepare you for the story of what happened to his body, because if you think that turning the story of a blown-up career into a best-case scenario is impressive, wait till you see what the Val Kilmer story-optimizer does with cancer.”

“The doctors did those other things, but it was the prayer that worked, he’s sure. He is no longer suffering from cancer, he said. Or rather, he never was. No, he’s suffering from something quite different. He pointed at his trach tube. “That’s from radiation and chemotherapy. It’s not from cancer.” His prayer, he said, was the true treatment; the medical response to cancer was the thing that hurt him. “That ‘treatment’ caused my suffering.”

“The margins on my suspension of disbelief started to close in on themselves, and the borders of things began to diminish, and now the world seemed like a word you stare at so long that it becomes nonsense. I watched all the Val Kilmer movies again, but this time they struck me as representations of a world that never existed, that couldn’t possibly exist: What is sweaty shirtless fighter pilot? What is dentist with tuberculosis? What is Downtown L.A. shootout? What is Batmobile? What is Lizard King?”

Finally, a quick link to one of my favorite of his characters he has played, one that almost sucked Val into a vortex, never to return (below: Danny Parker in The Salton Sea). A masterpiece of a film. Val plays a meth-head, but one on a mission I know you’ll like. Very suspenseful and clever. Like Icarus, Danny goes full-tilt and you can’t look away!